The Art of Optimization: Designing a Culture of Continuous Improvement

A Practical Framework for Implementing Process Optimization.

Optimization has long been treated as a technical exercise—a way to squeeze greater efficiency from existing systems. Yet, in an era defined by volatility, automation, and shifting human expectations, optimization has become something more profound. It is no longer about doing things faster or cheaper, but about designing systems that learn, evolve, and sustain excellence over time.

A process improvement plan, at its best, is not a static document but a living philosophy. It transforms operational fine-tuning into a culture of reflection, experimentation, and renewal. The following framework offers a way to reimagine process improvement as a strategic discipline, one that blends data with empathy, structure with agility, and ambition with sustainability.

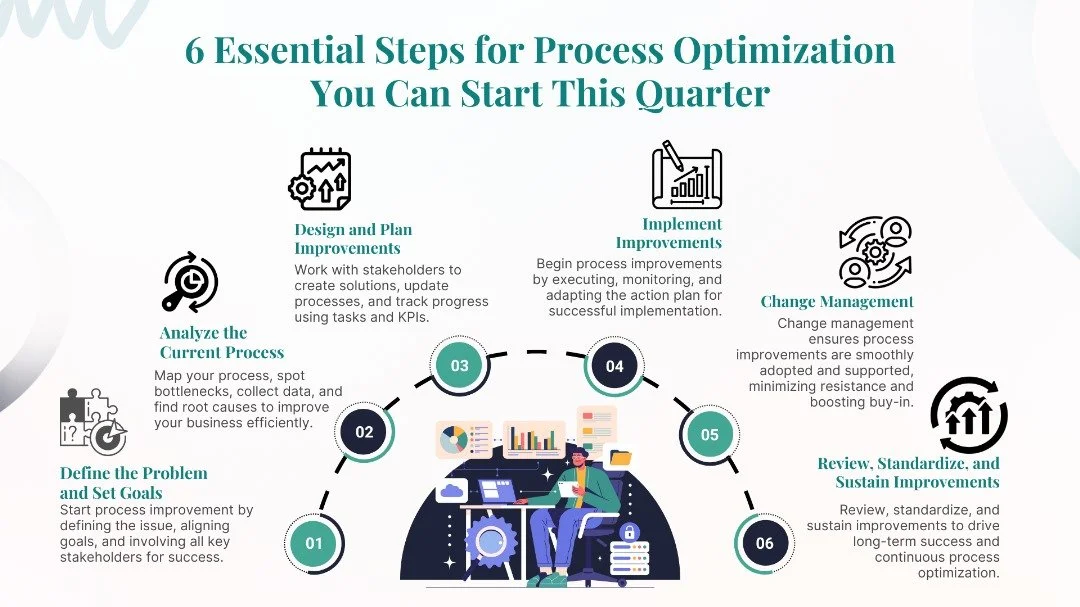

1. Define the Problem and Set Meaningful Goals

Every journey of improvement starts with the courage to define the problem honestly. Too often, organizations rush toward solutions before they’ve aligned on what truly needs to change. The first act of optimization is inquiry: What’s not working, and why does it matter?

Defining the problem is as much about conversation as analysis. Bringing together diverse stakeholders—those who run the process, those who depend on it, and those affected by its outcomes—creates a shared understanding of both pain and potential.

From there, goals should align with the organization’s broader strategy and values. Setting SMART objectives (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) turns lofty aspirations into grounded commitments. In doing so, improvement becomes not just a project, but a promise.

2. Analyze the Current Process with Curiosity, Not Judgement

Before designing a better system, we must understand the current one. Mapping a process is an act of discovery, a way to make the invisible visible. Diagrams, data, and direct observation reveal how work actually flows, where it stalls, and why certain outcomes repeat.

Collect both quantitative evidence (throughput, error rates, costs) and qualitative insight (employee frustrations, customer sentiment). The best improvement work doesn’t chase metrics; it listens to them.

Root cause analysis helps distinguish symptoms from structures. The goal is not to assign blame, but to uncover the patterns that quietly shape performance.

3. Design with Imagination and Discipline

Once the problem is clear, the work turns creative. Process redesign should be co-created with the people who live it every day. Their insights are not just valuable, they’re essential.

Develop a future-state workflow that addresses known gaps while honoring what already works. Innovation often emerges not from sweeping reinvention, but from small, intentional redesigns that compound over time.

Convert ideas into a practical action plan, one that defines tasks, timelines, resources, and success measures. Clarity in planning is not bureaucracy; it’s the bridge between aspiration and impact.

4. Implement, Observe, and Adapt in Real Time

Execution tests the resilience of ideas. Pilot new processes where possible to learn quickly and minimize risk. As implementation unfolds, monitor progress through well-defined KPIs, but remain open to the story behind the numbers.

Continuous feedback from employees and customers reveals how improvements behave in the real world. Deviations aren’t failures; they’re data. Adaptation, not perfection, is the true marker of operational maturity.

Optimization is not a linear process; it’s an ongoing conversation between intent and experience.

5. Lead the Human Side of Change

Process improvement succeeds or fails on one factor above all: people. The best-designed process means little if those who execute it aren’t ready—or willing—to embrace change.

Effective change leadership starts with empathy and transparency. Communicate not just the “what,” but the “why.” Anticipate resistance and treat it as dialogue rather than defiance.

Empower internal champions to model new behaviors and support others through the transition. Provide training, resources, and emotional space for learning. And when progress is made—celebrate it. Recognition turns momentum into culture.

Change, after all, is less about managing people and more about inspiring belief.

6. Sustain, Reflect, and Evolve

True optimization doesn’t end with implementation—it begins there. Compare new results against baseline performance and original goals. What worked? What surprised you? What remains uncertain?

Document lessons learned, update procedures, and refine workflows so improvements become institutional knowledge rather than personal memory.

Build systems for ongoing monitoring and reflection, ensuring that optimization remains an embedded habit. Recognize and reward teams that not only improve performance but sustain it.

Continuous improvement isn’t a cycle; it’s a mindset.

The Future of Optimization: From Process to Philosophy

In a world that prizes speed, optimization invites us to slow down just long enough to ask better questions, listen to better answers, and design better systems.

At its core, optimization is the art of alignment: aligning processes with purpose, technology with humanity, and improvement with impact. It reminds us that excellence is not achieved once—it is cultivated daily.

The organizations that understand this truth don’t simply optimize processes; they optimize the capacity to evolve.